High Inflation, Tariffs Fuel Thriving Black Market

Argentinean goods supply Bolivian stores in Santa Cruz and Cochabamba, driving prices down. (054)

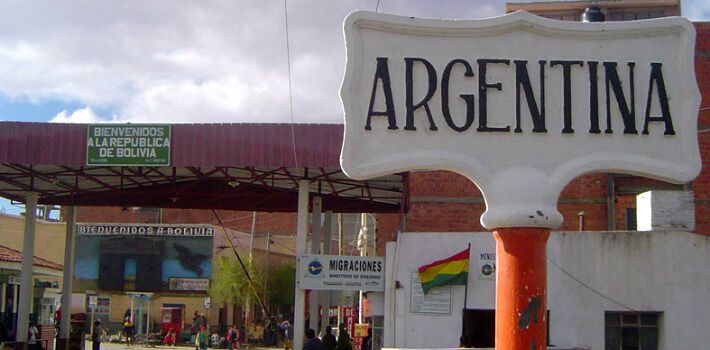

Amid vendors offering various fruit juices or traditional meals made with chicken or llama, hundreds of Argentineans and Bolivians cross the border everyday to buy goods at local street markets.

Argentina shares a border with Uruguay, Brasil, Paraguay, Chile, and Bolivia. To get to Bolivia, Argentineans have three international crossing points: La Quiaca passage in Villazón; the Aguas Blancas bridge, which connects Orán on the Argentinean side with Bermejo on the Bolivian side; and the Salvador Mazza bridge, which connects Araguay with Yacuiba.

It’s rare to find checkpoints or any sort of control. In 2014, the Argentinean TV show Journalism for Everyone reported that electronic scanners are turned off most of the time, and border officers are nowhere to be found. “If this is happening at legal crossing points, what’s going on at the illegal ones?” the journalists asked.

There are plenty of alternatives for those seeking a way around the official checkpoints. One is to hire a boat that will take you across the Bermejo river for just AR$4 (about US$0.4). For the more adventurous types, there’s the option to hop from stone to stone to reach the opposite shore, or dive into a subtropical forest path.

But in Araguay-Yacuiba, one of the hottest spots on the border with Bolivia, two other illegal passages recently emerged.

Yacuiba is a southern Bolivian city home to 92,000 people located only three kilometers north of the Argentinean border.

Across the Graveyard

Some 30 Bolivian “loaders” or bagalleros, who illegaly carry goods on their backs or in small carts to the other side, must hide from Argentinean officials patrolling a section of the border, so they cross it at a graveyard in Yacuiba. Once they reach the Argentinean side, they buy soybean, flour, corn, rice, and potatoes. For each cart successfully smuggled, the Bolivians receive 35 Bol. (around US$5).To not arouse suspicion, many smugglers simply pretend to visit a family member’s grave, or stand in the field watching the Argentinean side.

The other new curious way of crossing to Argentina is through a gulch five kilometers away from the international bridge, known for its nauseating smells coming from nearby cattle, sheep, and pigs.

The authorities estimate that over 1,000 locals cross the border illegally everyday, a process that usually takes around 15 minutes.

As Argentina’s economy tumbles, the peso’s depreciation over the years is driving the booming smuggling business.

Due to the volume of goods entering Bolivia on a daily basis, their selling price has plunged below production costs, claims Ronaldo Díaz Salek, head of the Bolivian Association of Oilseeds and Wheat Producers (ANAPO). He explains that this has discouraged Bolivian farmers to plant less profitable crops.

For instance, a kilo of rice went from 38 to 28 Bol., while 100 lbs of flour that use to cost 130 Bol. can now be found for 115 Bol.

Bolivians flock to Argentinean stores in Salvador Mazza. (Aerom)

Díaz Salek points out that the imported goods (legal or not) fall short of health and quality-control standards, lacking permits and licenses.

Bolivia’s National Service of Agricultural Health and Food Safety (SENASAG) announced an “aggressive policy” to patrol the borders and curb smuggling. So far this year, Bolivian authorities have seized 60 tons of food.

Isico López, a worker from Villamonte, a town a few kilometers away from Yacuiba, told the PanAm Post that he has crossed the Argentinean and Bolivian border many times.

“Bolivians buy Argentinean goods because they are cheaper; those who smuggle buy products for their families in Salvador Mazza. Likewise, Argentineans go to Bolivia to buy clothes, because they are cheaper there,” López explains.

Trade Begets Progress?

Agustin Etchebarne, head of the Argentinean think tank Libertad y Progreso, argued that free markets benefits both buyers and sellers in a transaction. He also explained that trade always goes both ways: where there is an export, there is an import, and vice versa.One way to obstruct free trade is through quotas and tariffs to make importing goods more expensive. Sometimes taxes are excessively high or prohibitions are put in place to discourage imports altogether.

“In many cases, demand is there, but it cannot be attended to because the product is unavailable. This situation creates great profit incentives for smugglers. Someone who takes the risk to smuggle in goods is simply supplying the demand for legal goods (parts, shoes, etc.),” he says.

No comments:

Post a Comment