Ricardo Hausmann

Ricardo Hausmann, a former minister of planning of Venezuela and former Chief Economist of the Inter-American Development Bank, is Professor of the Practice of Economic Development at Harvard University, where he is also Director of the Center for International Development. He is Chair of the World Eco… read more

CARACAS – Two years ago, public protests erupted in both Kyiv and Caracas. Whereas Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity quickly took power, political change in Venezuela followed a much slower path. But Venezuela’s parliamentary election on December 6, which gave the opposition a two-thirds majority, is moving political developments into the fast lane.

Although President Nicolás Maduro accepted defeat on election night, his government has promised to disregard any laws that the National Assembly enacts, and has appointed an alternative Assembly of the Communes not envisaged in the constitution. Moreover, he used the National Assembly’s lame-duck session to pack the Supreme Court and has called on supporters to prevent the newly elected Assembly from being seated on January 5. Like Ukraine two years ago, Venezuela is heading toward a constitutional crisis.

But there is an older and more ominous parallel between Venezuela and Ukraine: the Soviet Union’s man-made famine of 1933. Stalin’s decision in 1932 to force independent farmers – the kulaks – into large collectivized farms caused 3.3 million Ukrainians and ethnic Poles to starve to death the following year.

The catastrophe was unleashed when Stalin, convinced that the kulaks were hiding grain from the Soviet state, requisitioned the seed grain, believing that this would force the kulaks to use the hidden grain as seed. But there was no hidden grain – and thus no seed to plant the 1933 crop. Stalin blamed the ensuing collapse in food production on conspiracies by the dead and dying.

Instead of dealing with the unfolding catastrophe, Stalin increased grain requisitions, despite dismal production levels – a move that led to mass starvation. Information was hidden from the public, preventing remedial action. Even offers of international humanitarian assistance, especially by Poland, were rejected.

A famine in a country as fertile as Ukraine was hard to imagine before it happened. And it is hard to imagine a similar catastrophe in a country with the world’s largest oil reserves. But, heading into 2016, Venezuela faces precisely such a scenario.

There are four fundamental ingredients of such man-made disasters: repression of the market, suppression of information, systematic persecution of dissent, and attribution of blame for the disaster to the victims (which justifies radicalizing the policies that led to the problem in the first place). Sadly, Ukraine is not the only example: The human toll in China of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward of 1958-1961 was even greater, causing an estimated 15-45 million deaths.

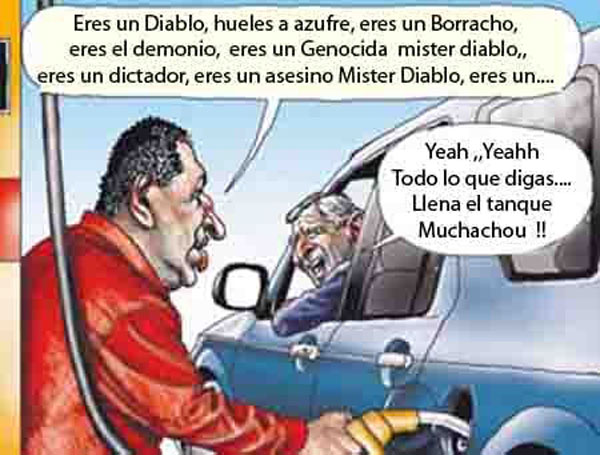

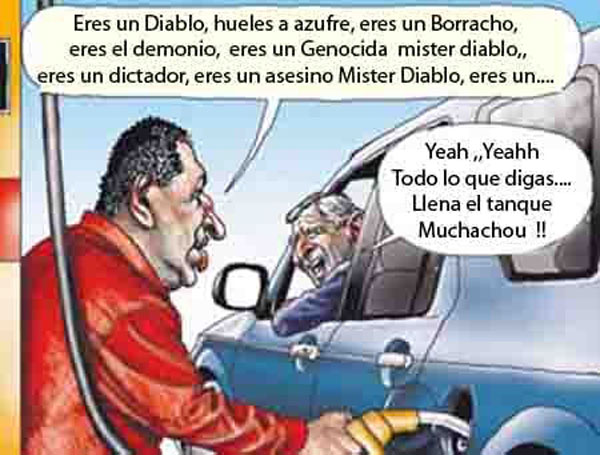

As in Ukraine and China, Venezuela’s government has been trying to collectivize production. After Hugo Chávez was re-elected in 2006, he decided to accelerate the “revolution” and nationalized banks, telecoms, cement, steel, supermarkets, hundreds of other firms, and millions of hectares of land. And, as in Ukraine and China, the affected firms’ output quickly collapsed.

Beyond outright expropriation, the government implemented a system that attacked the market’s natural ability to self-organize the economy. The market is no panacea, and it can work only with a state that operates properly, but it is a powerful stabilizing force. Market prices provide information about what is in short supply. Profits create incentives to respond to the information contained in prices. And capital markets allocate resources in pursuit of profits. Markets may fail, and policies can improve on outcomes; but Chávez and Maduro, like Stalin and Mao, attacked the market mechanism itself.

In Venezuela, a generalized system of price and foreign-exchange controls is causing havoc. Foreign exchange is allocated administratively at a price that is about 130 times cheaper than the market rate. Not even drug trafficking is as profitable as this arbitrage opportunity, with obvious consequences.

A formula for “just” prices keeps all prices artificially low (setting higher prices buys violators a ticket to prison), causing shortages, rationing, and queues that consume many hours of most Venezuelans’ days. Shortages of critical items have already cost many lives, not to mention the devastating effects on production. And, despite price controls, inflation is above 200%, because the central bank monetizes a fiscal deficit of more than 20% of GDP.

The rising oil prices that accompanied the adoption of these policies initially muted their impact, as imports could make up for the fall in output. In 1998, when Chávez was first elected, oil was languishing at $8 per barrel; in 2012, prices averaged $104.

But, rather than using the windfall to build a financial cushion for a rainy day, Chávez chose to use high oil prices as collateral to borrow massively, quadrupling the public external debt. This allowed him to spend in 2012 as if the price of oil were $197 per barrel. But now, with Venezuelan crude below $30 dollars and the country cut off from international capital markets, imports are declining to a fraction of their 2012 level. The previous destruction of productive capacity has come home to roost.

Without the market mechanism, the adjustment is taking place with too little information and too many perverse incentives, making its impact on production and welfare even more devastating. The coming year will see a further drastic cut in imports. Not only are oil prices even lower, but imports in 2014-2015 were financed in part by running down reserves and other assets, and by authorizing private imports but not paying for them, de facto expropriating the working capital – the seed grain – of private companies.

The implications of this madness are ominous. To prevent a humanitarian catastrophe, swift action needs to be taken: restoration of the market mechanism; exchange-rate unification (as President Mauricio Macri just implemented in Argentina); an alternative system of social transfers to substitute for rationing; fiscal retrenchment; orderly foreign-debt restructuring; and massive financial support from the international community.

Maduro is not trying to do any of this; instead, he is devoting his energy and creativity to maintaining power, by fair means or foul. But time is running out. Unless Maduro changes, the new National Assembly – where the opposition’s two-thirds majority enables it to amend the constitution – will have to change him.

No comments:

Post a Comment